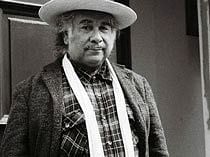

Q+A Tia Mavanie - UneARTh

15 November - 5 January

In conversation with Public Engagement Officer, Linsey GosperWhat motivates your choice of materials, such as cardboard, leaves, and wood, and how do these mediums align with or reflect the underlying concepts of your work?

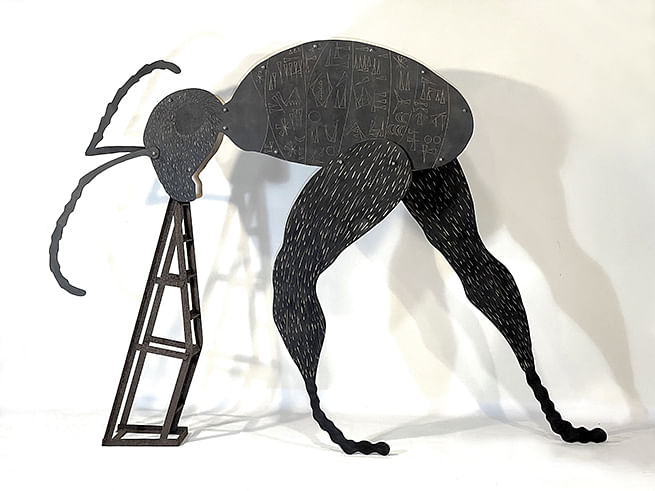

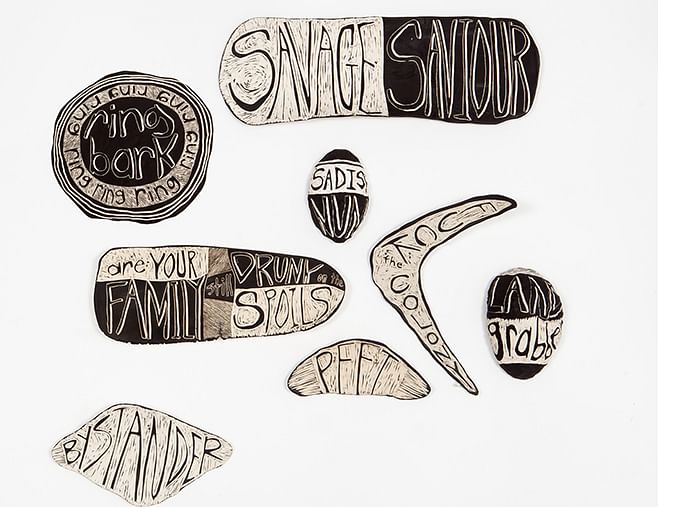

My choice of materials reflects a deep connection to both environmental themes and my Mesopotamian cultural heritage. Each medium serves as a symbolic extension of the themes of transformation, nature, and resilience that are central to my work. They not only symbolise sustainability, but also reflect the resilience and adaptability seen in Mesopotamian culture, where my ancestors thrived in harsh environments and creatively adapted available resources and practices that are still in use today.

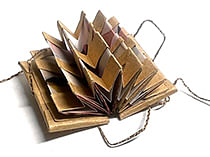

Cardboard echoes the impermanence of material culture, linking it to the erosion and loss of physical Mesopotamian sites, yet emphasising how their cultural memory endures. Leaves symbolise the cyclical nature of life, death, and renewal. Themes that are deeply embedded in my work and Mesopotamian mythology, where gods such as Inanna then Ishtar in later Assyrian culture experience death and rebirth. Nature was often intertwined with divine narratives, and leaves represent that connection to life force, fertility, and regeneration. The use of leaves also brings an organic, ephemeral element to my work, emphasising the fragility of existence. Wood was a precious and scarce resource in Mesopotamia, symbolising both value and transformation. By burning or carving wood, I invoke the duality of destruction and creation that was central to Mesopotamian cosmology, mirroring their use of fire in rituals and as a symbol of divine presence.

Together, these materials embody themes of interconnectedness, life, and transformation and allow me to engage with environmental themes of sustainability while honouring the deep-rooted cultural practices of my heritage. They serve as a bridge between the past and the present, allowing me to re-imagine and reconnect with my ancestry in a meaningful, material way.

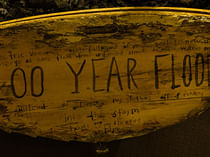

I am interested in your use of pyrography and its incorporation of fire, which often symbolises transformation, passion, and intensity. Was this symbolic use of fire a deliberate choice in your artistic process?

The act of burning timber works as a catalyst in connecting with my ancient ancestors, I use it as a tool to transform raw materials into art. It reflects the cycle of renewal inherent in life and nature, echoing themes in Mesopotamian mythology. For instance, fire's duality parallels Mesopotamian narratives of chaos (Tiamat) giving rise to order (Marduk), as an agent of both destruction and creation.

The use of fire serves as a personal dialogue with my Mesopotamian roots, exploring themes of identity, heritage, and transformation. The act of burning metaphorically rekindles this ancestral connection, drawing on fire as a bridge between the mortal and divine. Like cuneiform writing, pyrography inscribes symbols to tell stories, merging modern and ancestral identities.

Your exhibition includes research on ancient Mesopotamian sites and deities. Could you elaborate on the sources of your research and how you encountered this subject matter? Additionally, what is your personal or ancestral connection to these ancient traditions?

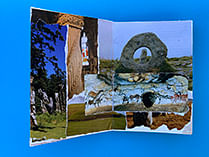

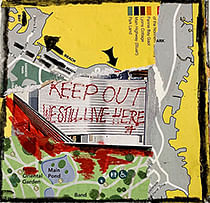

Motivated by the under representation of Mesopotamian culture in contemporary history and the lack of recognition of its global influence, as well as my family's survival through decades of genocide that continues in Iraq today, I sought to learn more about my heritage. The sources of my research are papers by Prof. Joel J. Elias, Prof. Simo Parpola, Prof. Stephanie Dalley, Prof. Amanda H. Podany and Prof. Marija Gimbutas. One of the publications I found particularly influential is ‘The Genetics of Modern Assyrians and their Relationship to Other People of the Middle East’ by Prof. Joel J. Elias which explores how recent advancements in DNA tracing technology reveal how the echoes of our human ancestors are recorded in the genes of present-day people, a concept that is imbued in my work. Three of the artworks represent ancient sites inspired by research into my family tree, which led me to Mavana, a village based in Urmia County (current day West Azerbaijan, a province of Iran), where my family name ‘Mavanie’ comes from.

In your exhibition, you reference the deities Inanna/Ishtar, which are believed to be precursors to the Roman goddess Venus. How do you perceive the similarities and differences between these figures, and in your view, what aspects of their significance have been diminished or altered in contemporary interpretations?

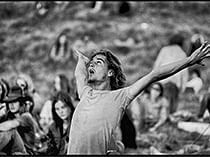

I aim to reclaim the multifaceted nature of Inanna/Ishtar, reintroducing her to contemporary audiences as the dynamic figure who was associated with the planet Venus and worshipped by the Sumerians, Mesopotamians, and the Assyrians for approximately 4000 years. She represents power as not inherently masculine or feminine, but a dynamic force that transcends gender. She embodies duality, both creation and destruction, beauty, and power, represented as a link between heaven and earth, masculinity and femininity, life, and death. She was known as the Queen of Heaven, an androgynous deity, who is believed to have had the ability to change a person’s gender. Gender was considered fluid in ancient times, those who did not fit strictly into the biological binaries were recognised for their remarkable powers and abilities. Androgynous individuals were respected as possessing a gift that allowed them to bridge the realm of opposites, the transitional space between chaos and order, masculine and feminine, which created balance, and helped to understand the unknown. They were seen as having divine powers, acting as agents of transformation and boundary-crossers. Their ability to navigate the space between binaries, was not just a social function but a spiritual one, deeply embedded in the myths and rituals of the time.

By tracing Inanna/Ishtar's evolution to the later goddesses of Greece and Rome etc, I highlight how cultural reinterpretations can simplify complex archetypes, and I invite viewers to reconsider the role of this deity in shaping not just ancient, but modern understandings of femininity and its relationship to divinity, and transformation.

In contrast, particularly in the west today, we don’t offer the same respect or recognition to the feminine, earth or androgynous, non-binary and transgender people, where debates over gender identity and body sovereignty continue to be contentious and increasingly volatile. In Iraq, violence and discrimination against women and LGBTQ+ individuals persist, with a climate of fear from persecution and even death preventing many from seeking justice or protection. In comparison to this, the inclusive and revered status of women and non-binary individuals in Mesopotamia serves as a poignant reminder of a time where once an egalitarian society thrived, respect for women and gender fluidity was celebrated and sacred, offering a valuable point of reference for current struggles for equality and human rights.

What insights do you hope audiences will gain, or what assumptions might they reconsider after engaging with your exhibition?

I hope audiences gain a deeper understanding of the complexity, resilience, and cultural significance of ancient Mesopotamian traditions, particularly as reflected through the lives of women such as Enheduanna the world’s first known author and the beloved Queen Kubaba. I also aim to challenge assumptions about the permanence of historical narratives and the roles of feminine archetypes in shaping cultural identity.

Many assume that ancient civilisations are relics of the past, disconnected from the present. My exhibition demonstrates how Mesopotamian traditions, symbols, and values continue to resonate in modern identity and art, fostering a sense of continuity. I hope the exhibition inspires audiences to see the past not as distant or fixed but as a living narrative that shapes and informs contemporary identity. I want them to leave with a sense of curiosity, about their own histories, the fluidity of cultural memory, and the power of art to bridge ancient and modern worlds.

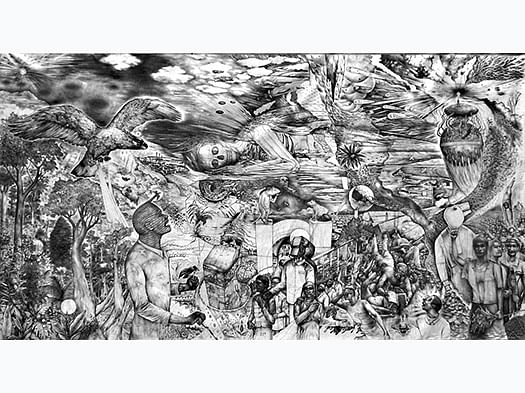

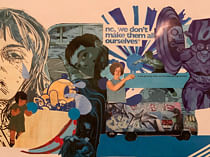

In the pyrographic portraits, there is a striking merging of flowers, snakes, leaves, and jewellery with the human face, almost as a form of shape shifting adornment. What do these symbolic elements represent within your work?

The merging of these elements reflects a shapeshifting quality, where the portrait becomes a canvas for the interplay of humanity, nature, and the divine power of transformation. This suggests a fluidity of identity, acknowledging that humans are constantly evolving beings shaped by their connections to heritage, environment, and spirituality. The adornments don’t just decorate; they transform, expressing the subject’s inner strength, vulnerability, and connection to the cosmos. Their ephemeral nature also speaks to the cycles of life and death, a recurring theme in Mesopotamian mythology. These symbols also speak to resilience and cultural survival.

The adornments transform the human face into a living testament to Mesopotamian traditions, reinterpreting motifs that have endured millennia of adaptation and reclamation in the face of loss and destruction. The artworks act as a bridge, reviving ancient symbols in a contemporary medium while exploring their relevance to modern identity. By merging these elements with the human face, I suggest that our heritage, like these adornments, is not static but an evolving part of who we are, a source of strength, beauty, and transformation.

By revisiting the past, we often uncover insights that resonate with our present. What wisdom or guidance do you believe these ancient deities can offer in contemporary contexts?

The ancient Mesopotamian deities offer more than just glimpses into the past; they provide timeless wisdom that can inform our contemporary world. From navigating personal transformation to fostering societal balance and environmental stewardship, their stories encourage us to embrace complexity, balance power with responsibility, and see ourselves as part of a larger, interconnected whole. In revisiting these deities and their mythologies, we tap into a deep well of insight that is just as relevant today as it was thousands of years ago.

Ancient Mesopotamian culture offers valuable insights that can resonate with modern society, particularly through its portrayal of female deities and early gender balance. While Mesopotamian society evolved over time, early stages often reflected a more egalitarian structure, especially in spiritual and mythological contexts.

Tia's exhibition UneARTh is on in Gallery 5 until January 5, 2025.

www.tiamavanie.com

_website_small.jpg)

.png)

smnall_web.jpg)

_web_small_2.png)